In 2019, the Operational Control Centre (OCC) is a standard facility across virtually all aviation companies with more than a handful of tails in the air. However, it wasn’t always like this.

Michael Arbuckle, CEO of OCC Tech Design, was there when the very first airline OCC was theorised, developed and built. And didn’t come about from a eureka moment from some corporate visionary.

No, it all happened when external factors wreaked a total collapse in business as usual operations at one specific airline.

Operational collapse

This airline (which will not be named) had an operational regime that had come about through ad hoc adaptations following its rapid growth from an aircraft fleet of a few dozen to a few hundred.

Its main hub went from handling 200 flights a day to more than 1000. Even on days when there were no disruptions, the existing procedures weren’t quite adequate to manage the volume of flight operations.

This led to an unspoken operational goal of accepting the status quo: if the team managed to just get by day-to-ay, it was enough.

However, one winter, a massive snowstorm hit and the airline’s hub airport was forced to close. Attempts to maintain control of the published flight schedules led to an operational meltdown.

All flights were either diverted or grounded. Some flights were sent to airports that had no aircraft maintenance capability, minimal passenger accommodation or insufficient fuel. One flight carrying 1 tonne of live lobsters landed in snow so deep that it couldn’t be unloaded.

Flight crews were reassigned, aircraft maintenance was rescheduled, the airline scrambled to accommodate passengers, scores of connections were missed, vacations were ruined. All 1,000kg of lobsters died.

In short, the airline’s operations were crippled and systemic vulnerabilities were laid bare.

Arbuckle says it took five days to sort it all out.

“A significant amount of frustration and stress was experienced by nearly everyone involved,” he says.

In the aftermath of the snowstorm, it became clear that “getting by day-to-day” was no longer acceptable.

“In fact, the status quo was no longer tolerated and was seen as a detriment to the airline’s future success.”

Approximately six weeks after the snowstorm chaos, members of the tactical flight operations team – whose jobs were to manage such events – met with executive management to present a theory of how to avoid such disruptions in the future.

In the following weeks input from people who were on duty during the snowstorm led to this theory evolving into a concept for what we now call an OCC.

The theory underpinning the OCC concept

As the initial theory evolved, it identified nine major factors in OCC design:

- Precise analysis of current practices

- Review of anticipated enhancements to those practices

- Consideration of IT, video and communication products

- Review of skill level of current and incoming staff members and their required training

- Identification of current or potential unchangeable limits that may prevent desired enhancements

- Consideration of physical location

- Securing construction contracts

- Selection of interior furnishings

- Consideration of potential expansion.

Arbuckle notes that the design of an OCC varies significantly based on an operator’s size, mission and scope. The design is also often influenced by the personal preferences of those who will staff the new OCC.

“The selection of specific departments invited to become a part of the OCC is based on the value of their input into solutions when disruptions occur,” he says.

“The strategic location of personnel within the OCC is very important due to the critical input many of the newly included departments provide to the OCC decision makers.”

From concept to creation

Arbuckle says that building that first airline OCC took two years. One of the big challenges was obtaining financing – after all, the design team was proposing something all-new.

Yet, after numerous presentations to management, what seemed to be adequate funding for the new OCC was granted and the building process began.

As the process moved forward, new and exciting ideas began to surface. These meant the project soon had to encompass:

- Unique software requirements from 17 separate departments

- More computers, printers and monitors

- A futuristic telephone system

- Multiple 3 square-metre video screens.

Costs spiralled. In the end, the world’s first airline OCC ran 800 percent over budget. While management understood the necessity of the OCC, they were nonetheless displeased at the pricetag.

“But we’d reached a point of no return on the project and nearly everyone involved – including the chairman – believed the solution was still warranted,” Arbuckle says.

When the state-of-the-art facility was completed, it was quickly nicknamed ‘The Star Wars Center’.

“I was as proud and hopeful as anyone present.”

When unveiled to media fanfare, the OCC leapfrogged the aviation industry in operations control. Bringing up to 20 departments together in one room, the OCC meant if a department had credible information regarding a specific operational dilemma, it was to provide this data to a decision maker.

This person could then take action with the fullest possible knowledge of operational status. Enabled by technology and the right management structure, this proved to be one of the greatest advancements in aviation operations control ever.

“The OCC had an 18-24 month return on investment and eliminated countless irregular operations previously determined by aviation management and the travelling public to be routine,” Arbuckle says.

“We now had proof that the OCC concept, when turned into a reality, is extremely efficient and effective.”

Applying the example in your operations

Arbuckle’s experience shows that what having a good OCC really means is your airline can rely on a facility for managing daily operations that has been specifically designed around current best-practice.

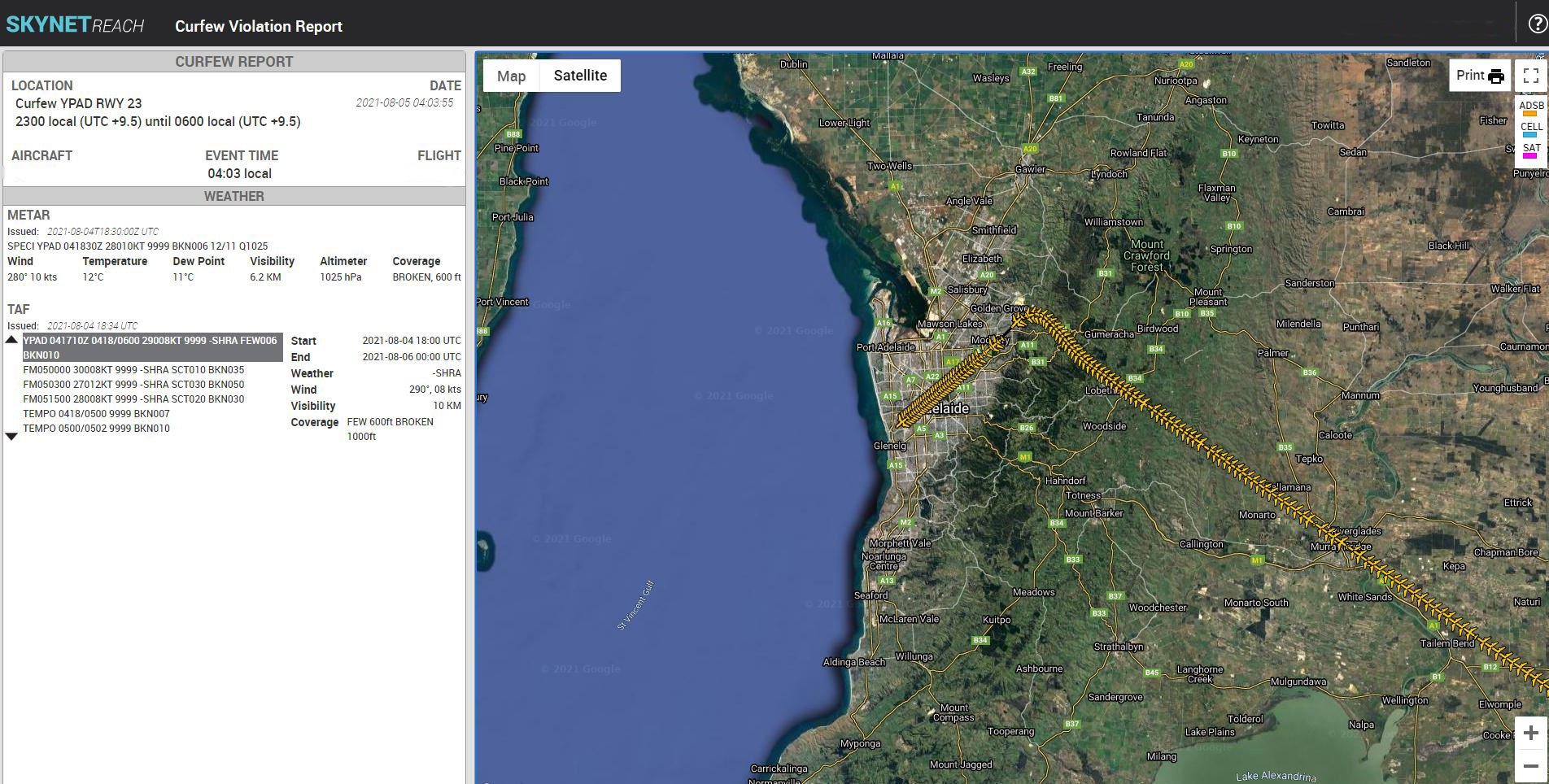

A properly functioning OCC will receive live data from several sources. This data fosters accurate decision making during normal operations and, when irregular operations occur, the OCC will know the circumstances sooner. Further, it will know how to return an irregular operation back to normal and do so efficiently.

Arbuckle says the example of the world’s first airline OCC showed that the benefits of this capability are virtually endless.

“It is now the gold standard for the professionals who manage flight operations at nearly every major airline, and at numerous minor airlines,” he says.

Not to say that an OCC is ever truly complete or 100 percent optimised.

“OCC evolution is common and necessary. Evolution of the OCC occurs when an airline refuses to accept the status quo as their ‘old’ procedures begin to fail and circumstances change making their current practices costly and obsolete,” Arbuckle says.

Throughout it all, the objective of the OCC must remain clear. It must be a highly efficient and highly effective facility that repeatedly pays for itself by enabling staff members – who work side by side with multiple departmental representatives and receive their input into various situations – to make decisions only after receiving all pertinent information.

“This process ensures that ‘the first decision is the right decision’. These procedures save time, money and provide the highest level of customer service,” Arbuckle says.“The cost to build your company’s OCC will be reasonable. The cost to your company not to build your OCC is massive.”